Overview

• India-Russia relations seek a revival

• Re-engaging on Afghanistan

• US & Russia spar and talk

India-Russia relations seek a revival

2020 and 2021 have seen a litany of commentaries on the health and relevance of the India-Russia relationship, prompted by the postponement of the annual summit in 2020, the India-China standoff in Ladakh, President Putin’s comments on a Russia-China quasi-alliance, Foreign Minister Lavrov’s intemperate comments about India’s Indo Pacific engagement, and Russia’s exclusion of India from its initiatives on Afghanistan. President Putin’s brief visit to India helped to temper some of the extreme narratives and to encourage a more realistic assessment of where the bilateral relationship stands.

The packed summit agenda included a joint commission meeting on defence cooperation (at defence minister level), a meeting of the foreign ministers, the inaugural meeting of the foreign and defence ministers in the 2+2 format, and finally a delegation-level meeting of the two leaders, followed by the now customary tete a tete over a meal (dinner), before the Russian President left, to prepare for his virtual meeting with US President Biden the next day.

The spadework for the visit was done in two telephone conversations of the leaders in April and August (Review, 4/21 & 8/21), EAM Jaishankar’s visit to Moscow in July (Review, 7/21) and two visits by the Russian NSA to India (Review, 10/21, and the following section). President Putin also set the stage on the eve of his visit, by describing India as “one of the authoritative centres of the multipolar world”, with which Russia had “a similar foreign policy philosophy and priorities”.

At their meeting, PM Modi paid tribute (as he and his predecessors have done in the past) to President Putin’s unwavering support for the bilateral strategic partnership. The personal rapport that the two leaders have developed over the past seven years was also amply in evidence.

The extensive Joint Statement missed a century of paragraphs by one. It covered an extraordinary breadth of sectors and subjects of cooperation, but in most cases as expressions of intent, rather than records of achievements. It is not clear how much real action will result from the 28 agreements, covering trade, energy, culture, intellectual property, accountancy, cyber-attacks in the banking sector, manpower, geological survey and education, among others.

Defence cooperation showed achievement and intent. A 10-year roadmap for cooperation was concluded, modalities for manufacture in India of the “Kalashnikov” assault rifles were finalized and the two sides agreed to accelerate the shift from trade to joint manufacturing and technology transfers, in line with India’s priorities. The reciprocal logistical support agreement, RELOS, was not signed, as expected earlier, but it was clarified that some technical (and not political) issues needed sorting out, and that it would be concluded soon. Defence Minister Rajnath Singh publicly acknowledged timely Russian military supplies during the height of the tensions with China in 2020.

The arrival in India of the first elements of the S-400 air defence system, roughly coinciding with the visit, served to demonstrate India’s strategic autonomy in military acquisitions. Periodical warnings from the US, that it would attract the sanctions legislation, CAATSA, have not stopped, though there are indications that US policy-makers want to find a way to waive the imposition of sanctions. CAATSA has national security exception clauses, which could be invoked. There is the precedent of the Russia-Germany gas pipeline, Nordstream 2; for which the US recently found a way to waive sanctions against its ally, Germany, that would have halted the completion and operationalization of the project. However, even assuming that a waiver for S-400 is forthcoming, it is an unsatisfactory situation for both India-Russia and India-US relations, if each major acquisition from Russia has to go through the uncertainty of CAATSA applicability or the humiliation of having to seek a waiver. A more sustainable arrangement needs to be worked out. The US annual waiver of the Pressler Amendment in the 1980s, to enable US military and other assistance to Pakistan, suggests a template.

The energy cooperation has progressed well. Indian companies have invested an estimated $15 billion in Russia’s hydrocarbons sector. Russia has invested about $13 billion in midstream and downstream projects in India. India’s GAIL has a 20-year, $25 billion LNG supply contract with Russia’s Rosneft. Indian investments in natural resources in the Russian Far East (for which a $1 billion line of credit was announced by Prime Minister Modi in 2019) are being finalized. Russian investments in the Indian petrochemicals sector are reportedly under negotiation. In recognition of the opportunities, an India Energy Office (IEO), representing five Indian hydrocarbon PSUs, was inaugurated in Moscow in 2021. The detailed project report for operationalisation of the Vladivostok-Chennai maritime corridor – another significant connectivity project – is also close to finalization.

There was a stronger focus on economic cooperation at this summit than in earlier meetings. This is a welcome recognition of the vast, unrealized potential. But it also reflects a political understanding that broad-basing the partnership, by strengthening the economic pillar alongside the defence and energy pillars, enhances its robustness and creates more manoeuvrability for India’s policy for diversification of military acquisitions.

As in the past, the goal of increasing trade turnover to US$30 billion (from the present paltry US$ 10 billion or so) by 2025 was articulated, and an increase of mutual investment (from the present US$ 35 billion) to US$50 billion. These are laudable goals, regularly articulated by the leaders over the years. They have not trickled down to the business communities or, for that matter, to the economic ministries, trade and investment facilitation agencies or banking circles, all of which need to recognize and exploit the opportunities. The problems of perceptions are on both sides. On the Indian side, there are additional misperceptions about Western economic sanctions on Russia, though major European countries, which have imposed the sanctions, are regularly showing significant growth in their trade and investment exchanges with Russia. In his opening remarks with President Putin, Prime Minister Modi said that the two sides should “guide” their business communities to achieve these targets. Whether and how this would happen bears watching.

The other barrier to trade expansion is poor connectivity. Again, the leaders’ desire to fast-track operationalizing the International North-South Transport Corridor is welcome, but needs to be measured against implementation. The same can be said of the agreement to fast-track negotiations for the Free Trade Agreement under negotiation between India and the Eurasian Economic Union – comprising Russia, Belarus, Kazakhstan, Armenia and Kyrgyzstan – which could provide further impetus to trade and investment.

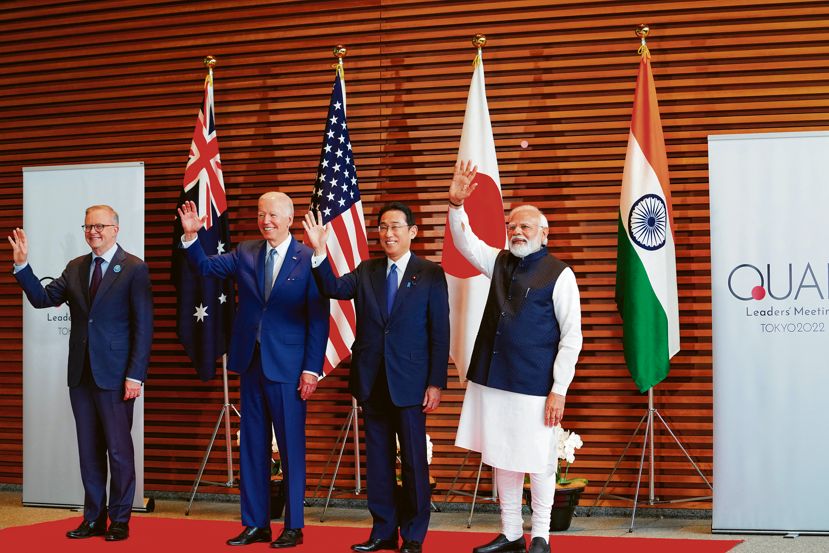

Despite the already broad India-Russia dialogue architecture, the 2+2 is a welcome addition. By sharing perspectives on global issues, clearing misperceptions and chalking out strategies to achieve shared objectives, the dialogue could enhance the strategic content of the relationship. It is the ideal forum to discuss Russia’s unease about India’s engagement in Indo Pacific initiatives, including the Quad and Malabar exercises. The challenge is to get across to Russia that India’s objectives in the Indo Pacific are compatible with President Putin’s ambitions for an independent Russian role in a multipolar world and his vision of a Greater Eurasian Partnership, now enshrined in Russia’s National Security Strategy 2021 (Review, 7/21). However, as long as US-Russia tensions remain high, Russia will continue to view US actions in the Indo Pacific as being aimed at both China and Russia.

Equally, China would have been discussed, both in the 2+2, as well as in the leaders’ tete a tete. Russia knows India’s concerns with the course of the Russia-China partnership, particularly concerning military technologies and intelligence-sharing. While details of the conversations on this would naturally be under wraps, there was a hint of Russian acknowledgement of India’s concerns in a public remark by President Putin to PM Modi that Russia’s military-technical cooperation with India is “like with no other partner” of Russia. This assurance (and its constant verification) is critical to the India-Russia partnership.

The summit therefore sought to re-energize the India-Russia partnership by emphasizing its main bilateral and external drivers. At the same time, some initiatives have been taken to broad-base the relationship, to reduce its heavy dependence on defence and energy cooperation. The big question is whether these initiatives will be effectively followed up: inadequate trickle-down of leaders’ stated objectives to the implementing machinery has so far been a persistent reality in both countries.

That the India-Russia relationship is not what it was in the past is a truism, bordering on the trivial. Political and economic transformations of the past two decades have ensured this. At the same time, to dismiss its worth and relevance is to adopt a geopolitical view from outside this continent. Defence collaboration and energy security are not passing fads. Initiatives for connectivity and security in India’s extended neighbourhood in the Eurasian landmass need different partnership templates from those in the maritime Indo Pacific domain. There is no need to compare or weigh bilateral partnerships; they stand on different pillars. With some diplomatic finesse, it is entirely possible to make separate partnerships compatible. Finally, policy-makers are well aware that public postures do not always reflect the underlying nature of great power relations: the post-Cold War geopolitical flux is constantly reshaping and recalibrating equations. These are the realities that inform India’s thrust for strategic autonomy – not nostalgia for an illusory past or an irrational attachment to the shibboleth of non-alignment.

Re-engaging on Afghanistan

The new phase in the India-Russia engagement on Afghanistan, after the Taliban takeover in Kabul (Review, 8/21), continued with a meeting on November 11 of the National Security Advisers of Russia, Iran and the five Central Asian countries in New Delhi at the invitation of NSA Doval, specifically to discuss the security situation in and around Afghanistan.

The principal message from the meeting was a rebuttal of the narrative of India’s marginalization in the regional dialogue on Afghanistan’s future course. What is relevant for the focus of this review is that the Russian NSA made it a point to attend, even though he had been in India for bilateral talks on the same subject just a few weeks earlier.

The declaration from the Delhi security dialogue (as it was called) underlined the convergence in their expectations from a new Afghan government, even though geographical, political and ethnic specificities may explain differences in their approaches and tactics: that it should be inclusive, uphold human rights and ensure that the territory of Afghanistan is not used to export terrorism or radicalization to any country in the region or beyond.

That Russia is simultaneously pursuing a separate diplomatic track was immediately highlighted by the meeting in Islamabad, just a couple of days later, of the ‘extended troika’ of the US, Russia, China and Pakistan, at the level of their Special Envoys for Afghanistan. The Taliban ‘Foreign Minister’ was also in attendance. The substance of the joint statement from that meeting (which is carried on the website of the US State Department) was much the same as that from the Delhi dialogue.

As in the case of the former US Special Envoy Khalilzad, his successor Thomas West emphasized the importance of cooperation with Russia on Afghanistan: he noted, in advance of the extended troika meeting that it was imperative to work with the region – with Russia, China, Pakistan, Iran, and the Central Asian states – “on our common and abiding interest in a stable Afghanistan” (note that India did not figure on this list). West attended the meeting in Islamabad, and then went to Moscow, before he came to India to debrief the NSA and the Foreign Secretary. He met his counterpart Kabulov and one of the Russian Deputy NSAs. These interactions took place in the midst of the heated exchanges between Washington and Moscow on the Russian troops on the Ukrainian border.

Meanwhile, the Russian security establishment (and President Putin himself) continued to stress the need to protect Central Asia from terrorism, extremism and “uncontrolled refugee flows” from Afghanistan. Actions to strengthen their military capabilities continued. At the same time, they were warned against succumbing to US persuasion to provide facilities on their territories for US over-the-horizon counter-terrorism operations in Afghanistan. In a media interview, Foreign Minister Lavrov said approvingly that Uzbekistan and Kyrgyzstan had publicly rejected this overture. He said that similar proposals were made to Pakistan, which also rejected them. Together with this certificate of good behaviour to Pakistan, he gratuitously added that he had heard that the US is “allegedly trying to persuade India to provide the Pentagon with certain capabilities on Indian territory”.

US & Russia spar and talk

This Review for 10/21 described the flurry of bilateral activity from September onwards, that appeared to be leading to US-Russia accommodation in some areas. The US Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff and his Russian counterpart discussed de-confliction in various geographies, where the paths of their forces or their proxies might cross, and (reportedly) possible cooperation to counter potential security threats emanating from Afghanistan. US Under Secretary of State Victoria Nuland had discussions in Moscow with a Deputy Foreign Minister and with two key Putin aides in the Kremlin, on a range of bilateral differences, as well as the vexed Ukraine issue. CIA Director Burns also paid a two-day visit to Moscow in early November, when he met his counterpart, as well as the Russian NSA, and got the rare opportunity of a conversation with President Putin. Meanwhile, US and Russian delegations, meeting in Geneva, reported reasonable progress in their talks on strategic stability (arms control) and cybersecurity issues. Russia and the US were on the same page on salvaging of the Iran nuclear deal. (See Review, 10/21)

Though reports had already surfaced in the western media of a Russian troop build-up on the Ukrainian border, the Russian Foreign Ministry denied them and, remarkably, the Ukrainian Defence Ministry also issued a statement, confirming that there was no unusual Russian military activity near Ukraine’s borders.

However, over the next couple of weeks, reports of Russian troop build-up merged with allegations of Russian efforts to politically destabilize Ukraine from within. Official reactions from across Europe and the US increased in tone and intensity, with the US, EU and NATO threatening additional, harsher sanctions on Russia, if it invaded Ukraine.

Russia persistently denied any intention of invading Ukraine and, in turn, alleged that Ukraine has concentrated some 125,000 troops on the border with rebel-held territory in that country, that military instructors from NATO are helping to strengthen military infrastructure there, and that the movement of US guided-missile destroyers and strategic bombers in and over the Black Sea posed serious threats at Russia’s borders.

In a major foreign policy address on November, President Putin dwelt on the broader context of the current tensions. Describing the Ukrainian crisis as among the most sensitive issues for Russia, he bemoaned Ukraine’s refusal to implement the Minsk agreements, the “indulgence” of France and Germany in permitting this, and the exacerbation of tensions caused by West’s supply of lethal weaponry to Ukraine. He said the West was totally insensitive to Russia’s security “red lines”: NATO’s military structure has virtually reached Russian borders, with anti-missile defence systems deployed in Romania and Poland, which could easily be put to offensive use with the Mk-41 launchers there – “replacing the software takes only minutes”. Asserting that Russia is taking appropriate military-technical measures for the present, he said it is imperative for Russia to seek “serious long-term guarantees that ensure Russia’s security in this area”. These guarantees, as he elaborated in a subsequent speech, should take the form of concrete agreements, ruling out any further eastward expansion of NATO and the deployment of weapons systems in close proximity to Russia’s territory. They need to be legally valid agreements, since verbal commitments have not been kept in the past (a reference to the assurance given to Gorbachev, in return for Soviet acquiescence to the unification of Germany, that NATO would not “move an inch” eastward). “We understand”, he said, “that any agreements must take into account the interests of both Russia and all other states in the Euro-Atlantic region”.

President Putin’s comments and tough words from NATO and EU Foreign ministers formed the backdrop for the second meeting, this time virtual, between Presidents Biden and Putin, on December 7.

US briefings on the meeting highlighted five major points. The first, of course, was the stern US warning that, in the event of any further military escalation by Russia, the US and its allies would take strong economic and military counter-measures. The latter, it was clarified, would take the form of reinforcing the military capabilities in the NATO countries on Russia’s periphery, particularly Romania and Poland (but not additional American boots on the ground). Second, such a military escalation would destroy the prospects of the Russia-Germany Nord Stream 2 gas pipeline being operationalized. Third, if Russia de-escalates, the US would be willing to work with its European partners, and alongside the Normandy process (involving Russia, Ukraine, France and Germany), to fully implement the Minsk agreements for a political settlement of the Ukraine impasse. Fourth, if Russia de-escalates, the US and its European allies would engage in a discussion that covers larger strategic issues, addressing the security concerns of the US, NATO and Russia “through a larger mechanism”. And finally, the two presidents tasked their teams to follow up on the issues discussed.

America’s “iron-clad” support for Ukraine’s sovereignty and territorial integrity was of course reiterated, as has been de rigueur in any US statement involving Ukraine in recent years. The briefings also drew attention to positive trends in the ongoing bilateral dialogues on strategic stability and ransomware, as well as a “productive” discussion on Iran and convergent views on the Armenia-Azerbaijan dispute.

The Kremlin’s readout of the conversation naturally had different emphases, but was not inconsistent with the US version. Ukraine’s “provocations”, NATOs advance and the need for mutual security agreements were all mentioned. President Biden’s focus on Russian troops near the Ukrainian border and his threat of sanctions in the event of further escalation was noted, alongside President Putin’s complaint about NATO’s dangerous inroads into Ukraine.

President Biden held a conference call with select European leaders (France, Germany, UK and Italy) before his conversation with President Putin; he also debriefed them after the conversation. The President and his European colleagues were said to have agreed that they would work in close coordination in their future engagement with Russia.

It is clear that, behind the scenes of the sabre-rattling and mutual recriminations, some quiet diplomacy and patient groundwork were already at play. The discussions in Moscow of Under Secretary Nuland and CIA Director Burns (see Review, 10/21) would have been part of it. From Russia’s perspective, the public acknowledgement of its security concerns from NATO’s deployments and actions on its periphery, and the stated US commitment to address them, was an important outcome of the Putin-Biden conversation. American reiterations of support for full implementation of the Minsk agreements by both sides, recognizing that there were shortfalls on both sides, would have been welcome.

The apex-level conversation has been followed up with telephonic contacts between US NSA Sullivan and the Russian Presidential foreign policy adviser Ushakov and between Secretary Blinken and FM Lavrov. US Assistant Secretary of State Karen Donfried has just concluded a round of consultations in Moscow, Kyiv and Brussels. Both Ukraine and the proposed European security dialogue were on the menu. A draft US-Russia treaty and a draft agreement on security measures by Russia and NATO were both handed over to her in Moscow. Detailed proposals have also been shared with the US on the way forward in the Ukraine crisis. A State Department official confirmed that these proposals are being studied, in consultation with European allies and with Ukraine, asserting that nothing about European security would be decided “without Europeans in the room” – a practice that the US has not always scrupulously followed over the years. The State Department also reconfirmed President Biden’s commitment to the principle of “no decisions or discussions about Ukraine without Ukraine”. Again, many in Ukraine may feel that, in the recent past, this principle has been more honoured in the breach than in the observance.

The logic of prioritizing dialogue over confrontation is obvious for both the US and Russia. The Biden White House has been consistently signalling that the US should shed unnecessary encumbrances to focus more fully on domestic challenges and the political, economic and security threats from China. A modus vivendi with Russia that moderates tensions in the European theatre and blunts the sharp edges of their confrontation in geographies across West, Central and East Asia would contribute significantly to this objective. For Russia, “normalization” of relations with the West would reopen the doors to engagement that can revitalize its economy and dilute its overwhelming dependence on China. Western sanctions may not have crippled Russia’s economy, as often projected, but they have severely constrained investments and growth in some critical sectors of the new economy, fuelling public discontent over falling living standards. COVID-19 has exacerbated this trend.

As frequently highlighted in earlier editions of this Review, the complex interplay of interests in the US and Russia, as well as within and between European countries, means that the progress of these baby steps in the direction of tension reduction may be halting and uneven.

*******

The previous issues of Russia Review are available here: LINK

…………………………………………………………………………………………………………………

(The views expressed are personal)

The Author can be reached at raghavan.ps@gmail.com

…………………………………………………………………………………………………………………