Overview

- Russia’s Coronavirus campaign

- Foundations laid for Putin Mark V & VI

- Russia-Saudi oil spat aggravated Covid impact on energy markets

- Snippets: Covid diplomacy, Idlib peace, Putin-Modi telecon

Russia combats Coronavirus

After relatively low incidence of detected Covid-19 cases in the first half of March, Russia announced a spike on March 24 (with 163 new cases). After visiting a newly created medical facility and holding a live televised discussion with medical specialists there, President announced in a national address on March 25 that the week beginning March 30 would be a “holiday week”, with all nonessential businesses closed down. He echoed the advice of doctors for the public to stay home and strictly observe social distancing norms. In the televised discussion, Russian doctors advised that for Russia to minimize damage to public health and economy, it was advisable to learn from the Italian example and to follow the China/Korea model of strict and early lockdown. The Russian parliament is reportedly drafting emergency legislation to enable fines and imprisonment for quarantine violation.

The disease has not yet assumed pandemic proportions in Russia: by the end of March, officially recorded confirmed cases were about 1850 (about 13 per million of population), with 9 fatalities. The Russian Defence Ministry is deploying troops to conduct field exercises on emergency response readiness and setting up “infection containment centres” in various regions to tackle the contingency of mass transmission.

There has been speculation about reasons for the relatively low incidence of the disease in Russia, besides the suspicion of some under-reporting. Particularly remarkable are the low figures in the Russian Fareast, with its 4200 km border with China, across which trade flourishes. The fact is that most of the border crossings had been quietly shut early in February, trade largely halted and Chinese workers encouraged to go back. Russian media has also noted that the Chinese tendency to create their own settlements separate from the local population helped to contain transmission. As noted in the Review for February, local authorities even in Moscow went to extreme lengths to screen Chinese in public places, looking for evidence of the virus. Russia closed its international borders on March 16. The further fact that Western sanctions have severely restricted travel between the West and Russia (including Russians vacationing in European beaches) may have also contributed to relative Russian insulation from the disease.

In his address to the nation, President Putin announced a number of measures to cushion the economic impact of the lockdown on vulnerable segments of the population. They included social security benefits, enhancing and frontloading childcare benefits, rescheduling of EMIs and mortgage payments, tax breaks for MSMEs and a six-month moratorium on debt collections and bankruptcy proceedings. He also announced two new taxes to partially cover the expenditure on these socioeconomic measures. One was a 15% tax on repatriation of dividends (up from 2%). He said this could mean renegotiation of some double taxation avoidance agreement, failing which Russia would unilaterally withdraw from them. The second is a 13% tax on interests/dividends from term deposits/debt securities of above 1 million roubles (about $ 15000).

Russian economists estimate that the financing needed from the Russian government over the next few months to cover the Covid-19 relief measures, as well as the major socioeconomic programme unveiled by the President in January (see RR, 1/20) would initially be of the order of about a trillion roubles (about $ 14 billion) a month. The IMF review of the Russian economy in November 2019 showed a comfortable fiscal situation, with low national debt (thanks to Western sanctions) and liquid foreign exchange assets approaching 7 % of GDP (because of surplus oil revenues over the years having been put away). Subject to the intensity and length of the Russia-Saudi oil spat (see subsequent section), therefore, Russia would have the fiscal space to meet this burden. Curiously, Russia’s GDP recorded its highest recent growth (annualized rate of 2.9%) in February 2020.

Constitutional amendments moved

President Putin’s State of the Union address in January 2020 attracted global attention for the portions which seemed to offer a clue to his post-2024 plans (after he completes the final term of his Presidency, as per the current Russian constitution). Discounting the widespread speculation about a future role for him in the State Council or the Security Council, this Review (1/20) had drawn attention to his ambiguous comment on the constitutional cap of two Presidential terms: noting that people are discussing it, he said he does not regard it “as a matter of principle”, though he supports and shares this view. In the same address, he had also emphasized the need for a strong Presidency and elements of his suggested constitutional amendments included greater Presidential control over the federal and regional judicial system.

An expert committee charged by him to draft the constitutional amendments to give effect to the changes suggested in his January address came up with a number of variants on Presidential terms. President Putin addressed the Duma (lower house) to pronounce his views on them. He drew attention to Russia’s vulnerability to external machinations targeting its political stability, ethnic and religious accord, as well as its economic development. At this critical stage, he declared, Russia needed a strong President, with strong Presidential powers to ensure the country’s security and domestic stability. The day would hopefully come, he said, when Presidential power in Russia will not be linked to one individual, but one cannot ignore the fact that it has been so in Russian history. Russia, he said, cannot afford the weaknesses of western parliamentary democracies.

Having established the case for his own continuation, President Putin proceeded to identify a methodology by which it could be done. He rejected the suggestion of a Constitutional amendment providing for him to stand for re-election. He also felt removing the cap of two consecutive terms would be inappropriate. This provision, he said, should remain, since the constitution is for the long-term – 30 to 50 years – and he expects that, at some time in this period, the situation in Russia would stabilize and, at that stage, “society must have guarantees for a regular change of power”. For the present, he accepted the amendment that would set the clock back to zero – thereby lifting restrictions against him standing for election again (and the two-term limitation would count from then onwards). He added the caveat that this provision could be included only if the Constitutional Court ruled that it was not violative of the fundamental tenets of the Constitution. Unsurprisingly, that court gave a positive verdict very soon after the Russian parliament voted on the package of constitutional amendments, which included also the other amendments proposed in the President’s January address.

A referendum was scheduled for April 22 to ask the people to confirm all the amendments. The advance of Covid-19 has necessitated an indefinite postponement of that vote.

Russian opinion polls showed that among the various constitutional amendments that would be covered in the referendum, the ones guaranteeing quality of medical care, childcare benefits, indexation of pensions and other social security provisions were overwhelmingly popular, securing over 90% public support. Provisions to strengthen defence of the country’s territorial integrity and data protection secured over 80% support. However, a considerably smaller proportion (61%) supported the provision for lifting restrictions on the current president to take part in future presidential elections. This reflects the hit that President Putin’s popularity has taken in recent months, due to public unhappiness over recent decisions on taxation, increase in corruption at the federal and local levels, and inefficient delivery of social benefits. Russia’s handling of Covid-19 and the implementation of the major socioeconomic programmes announced in the January address could move the needle in either way.

Breakdown of OPEC+ consensus

A sudden and dramatic breakdown of the Russia-Saudi Arabia understanding on the OPEC+ regulation of the global oil production threw oil markets into total disarray, just when the Covid-19 impact was beginning to bite. The 2019 production cuts agreed between OPEC and Russia-led non-OPEC countries were due for renewal in April. Oil prices had already declined by about 20% in early 2020, due to Covid-19 and a lower winter demand in the Northern Hemisphere. Saudi Arabia proposed an output cut of 1 million bpd by OPEC and of 500,000 bpd by non-OPEC countries, but Russia demurred. Russia’s argument was that the production cuts benefit only the American shale oil producers, who have progressively increased their share of the global oil market at the expense of OPEC+. Falling oil prices were beginning to drive some shale oil producers out of business; hence the time was not ripe for measures to support the oil price. Offended by this Russian rebuff, Saudi Arabia immediately announced a huge increase in its output to 12.3 million bpd from the current 9.8 million bpd and offered discounts to Russia’s oil customers. Russia reacted with a decision to increase its output by 300,000 bpd. Global oil prices crashed, with Russia’s Urals crude falling below $20 at one stage.

Economists are divided about where the balance of misjudgement lay in this price war. Most have pointed out that in the short term, Russia has greater cushion against the impact of plunging prices. Its budget is based on an oil price of $42 per barrel, while that of Saudi Arabia assumes a price of around $80. Russia’s foreign exchange reserves, its current account surplus, its national wealth fund (consisting of accumulated excess revenues from oil exports) and arrangements with its cash-rich oil companies for bridging the federal budgetary gap due to falling oil prices, improve its staying power in a price war. Most importantly, rouble devaluation compensates in large part for oil price fall, since the production costs are almost entirely in roubles. Saudi Arabia does not have the same flexibility of exchange rate, since its riyal is pegged to the US dollar.

The longer-term direction is less clear, including for the US shale oil industry. Neither Russia nor Saudi Arabia can politically afford their socioeconomic programmes to become hostage to the price war. Also, the financial woes of shale oil manufacturers is not good news in a US election year. The US announcement that it would buy about 80 million barrels of crude from domestic producers to boost its strategic oil reserve reflected this sensitivity. There were reports that President Trump may intervene with Saudi Arabia to reverse its decision to increase production. A vague threat also hung in the air of further US sanctions against Russia that may hamper its oil exports. Meanwhile, the worldwide demand slump caused by Covid-19 meant that even deeply discounted Saudi crude could not find ready markets.

Snippets

Covid diplomacy: President Putin telephoned the Italian PM on March 21 and, in response to the latter’s request, offered assistance in dealing with Covid-19. Within the next week, at least fourteen IL-76 aircraft of the Russian Air Force delivered masks, hazmat suits, truck-mounted units for disinfectant spraying, and other medical equipment, in addition to over 100 virologists and epidemiologists. This assistance was of course given full publicity in the Russian media, which showed the Italian Foreign Minister receiving one of the Russian planes. European media commented that NATO and EU assistance had been upstaged and pointed to the geopolitical significance of the Russian assistance being coordinated by its Defence, rather than its Health, Ministry. The EU High Representative, Josep Borrell, urged Europeans to see through the “politics of generosity” – referring to both Russian and Chinese assistance. Italian officials responded blandly that Russia’s assistance was invaluable at a time of dire need.

Fragile peace in Idlib: As briefly indicated in Review 2/20, Presidents Putin and Erdogan patched up their differences over Idlib in early March, after about a month of verbal and military confrontation. They agreed on a ceasefire, a security corridor on either side of the strategic highway M4 in Idlib province (connecting Damascus with Aleppo), and joint Russian-Turkey patrolling of the highway. Russian official sources confirmed that the ceasefire was largely holding and that a joint patrol was successfully completed towards the end of March. However, indications are that, while Turkey may have been pushed on to the backfoot in this manoeuvre, President Erdogan has not given up his ambition for military control over the Kurdish-dominated regions along Turkey’s southern border. He has made fresh overtures to both the US and EU to secure their support. The threat of more Syrian refugees flowing across the Turkish border into the EU (with the additional fear of Covid infection) is a potent argument to focus EU attention on Syria. President Erdogan has also talked about persuading the withdrawing US forces to cede control of the oil-rich areas of Northeastern Syria to Turkey to enable relocation of Syrian refugees now in Turkey and to finance Syrian reconstruction. The fate of these initiatives has to await the aftermath of Covid-19.

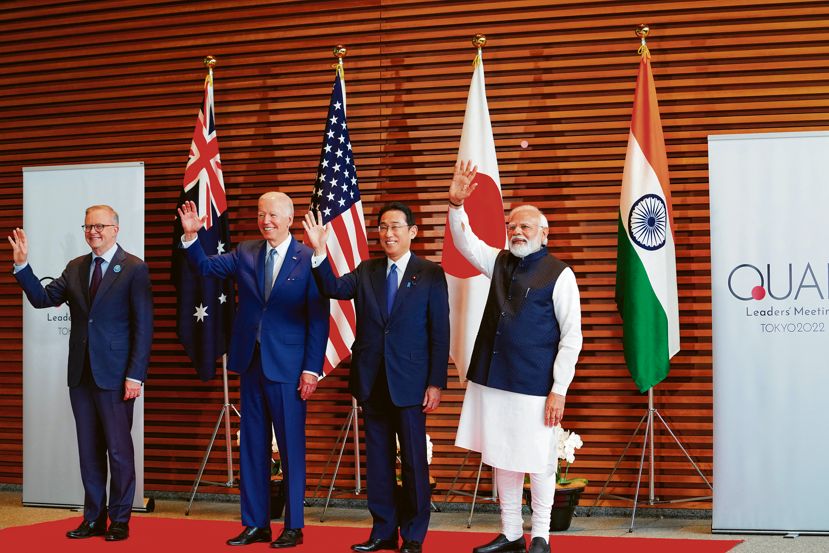

Modi & Putin discuss Covid & G20: Prime Minister Modi telephoned President Putin on March 25, in advance of the virtual G20 Summit on March 26. The Kremlin said the leaders briefed each other on their measures against the spread of Covid-19, expressed mutual appreciation for their efforts to protect the health and safety of Russians in India and Indians in Russia, and agreed to strengthen coordination in the coronavirus response effort. India’s PMO elaborated that they agreed on further consultation and cooperation in tackling Covid challenges pertaining to health, medicine, scientific research, humanitarian matters and impact on the global economy.

*******

…………………………………………………………………………………………………………………

(The views expressed are personal)

The Author can be reached at raghavan.ps@gmail.com

…………………………………………………………………………………………………………………