Votes, Violence, and Valuable Minerals: Myanmar’s Elections Amidst Civil War and Rare Earths Race

The world depends on China for its critical minerals needs but China, in turn, depends on a remote state in war-torn Myanmar. Myanmar holds one of the world’s largest reserves of heavy rare earth elements (HREE), supplying 57% of China’s total rare earth imports in 2024, which are essential in the production of advanced defence systems and green transition technologies like electric vehicles and wind turbines. Under the second Trump administration’s intensified focus on critical minerals, the US appears to be turning its attention to the region. India, too, has shown interest, by exploring partnerships with ethnic armed organisations despite a strong and steadily deepening relationship with the Tatmadaw (Myanmar military). Much of 2025 has been eventful for Myanmar with the sudden election announcement amidst an ongoing civil war and fast-paced evolution of engagements with China, the US, and India.

China’s Growing Reliance on Myanmar’s Rare Earths

While China dominates nearly 90% of global critical mineral processing capacity, it is less widely recognised that its supply of certain HREEs, particularly dysprosium and terbium, is significantly reliant on resources extracted from Myanmar’s Kachin State. Since 2017, China’s HREE imports from Myanmar have increased exponentially because of low extraction cost and lack of environmental regulations.

Ever since the civil war erupted in Myanmar in 2021, following a coup and crushed civil disobedience movement, China’s supply of HREEs have remained at risk. Following the seizure of major mining areas in Kachin state by the Kachin Independence Army’s (KIA), an ethnic armed organisation, China temporarily halted HREE imports from Myanmar by closing border gates. After negotiations, imports resumed under KIA tax regulation at a fixed price in April 2025, transforming Myanmar’s conflict economy and giving a non-state actor effective control over a key global supply corridor in a volatile region.

Trump Administration’s New Approach to Myanmar Sanctions

A sequence of developments beginning in early July 2025, although claimed to be unrelated by US officials, underscores a shift in American policy towards Myanmar, still referred to as Burma on most US government platforms. General Hlaing, Myanmar’s de facto leader who seized power from the democratically elected government, wrote a multi-page laudatory letter to President Trump requesting for lifting of sanctions and drawing a parallel between alleged electoral fraud in both countries in 2020 which he claimed had led to the losses of their respective parties. The letter was written in response to President Trump’s earlier correspondence regarding increased tariffs to several countries, including Myanmar.

Just a few weeks later, the US lifted sanctions on close associates of the Tatmadaw. And a few days after that, reports of competing propositions on sourcing HREEs from Myanmar — with KIA which is presently in control of most mining areas or, alternatively, with Tatmadaw — were heard by the Trump administration. However, this potential collaboration is highly impractical due to the technical and logistical challenges, such as lack of processing & refining capability and transport corridors, among other reasons.

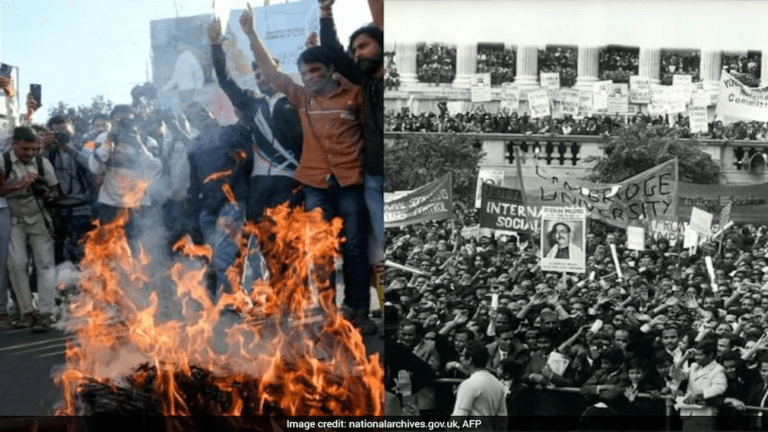

Myanmar’s 2025 Vote: Legitimacy in Question

Since this communication, Myanmar authorities have nominally lifted the state of emergency while retaining martial law, transferring power from the State Administration Council to the newly formed interim government, both headed by General Hlaing. Elections have been announced to begin on 28 December 2025 even as the civil war is ongoing, casting a doubt on the feasibility of a peaceful and legitimate political process. The election has been boycotted by several major political and armed groups. These moves have not been welcomed by reform advocates as steps towards democracy, but rather viewed as a tactical rebranding effort, perhaps, to seem more palatable to the US and the world.

In order to re-legitimise authoritarian rule, a new draconian electoral law was enacted right before the announcement of the upcoming national election. It entails harsh penalties, including death penalty, for those who oppose or disrupt the election. The electoral design also clearly favours Tatmadaw control. While all Lower House seats will be contested, many Upper House and regional constituencies, mostly in ethnic minority areas, will remain vacant, citing security concerns. This weakens the opposition’s ability to form a presidential coalition, and eases the path for a Tatmadaw-backed president.

Even prior to the 2021 civil war, Myanmar operated under constrained democracy as the 2008 Constitution, practically written by the Tatmadaw, ensured that veto power and 25% of the seats remain with them along with key ministries like defence and home affairs. It also prohibited Aung San Suu Kyi, the most popular leader in Myanmar, to become the president as evident in article 59F which was specifically enacted for her.

Myanmar’s Diplomatic Tightrope: Balancing China and the US

The Tatmadaw is attempting to play both sides by optimising its leverage to maintain favourable ties. A Washington-based lobbying firm has signed a $3 million-per-year agreement with Myanmar to help restore ties with the US. Concurrently, General Hlaing attended the SCO summit, where he also conducted a meeting with Prime Minister Modi; China’s Victory Day parade; and a series of meetings to boost trade & investment with China.

China’s participation in Myanmar’s critical mineral sector reflects prioritising economic and strategic interests without the constraints imposed by strong commitments to democratic governance, environmental protection, and labour standards. The US, too, seems to be deprioritising democracy in Myanmar, as it softens its stance on the Tatmadaw and considers options to capitalise on the attractive yet unrealistic potential opportunity of supply of critical minerals.

India’s Nascent Interest in Myanmar’s Rare Earths

India signaled its interest in Kachin’s resources when state owned India Rare Earths Limited (IREL) and Geological Survey of India officials visited the region and conducted meetings with the KIA to evaluate upstream collaboration opportunities in late 2024. An intense ongoing battle starting in December 2024 in Bhamo, a key military and logistical hub in Kachin State, has become a flashpoint, with China allegedly pressuring the KIA to halt its offensives. By August 2025, the Tatmadaw had reportedly regained control of the strategic town, located south of key mining zones. This shift may have influenced the KIA’s recent willingness to consider mining partnerships with India. In a further development, as of September 2025, India’s Ministry of Mines has instructed both state-owned and private firms to assess the viability of sourcing and transporting HREE samples from KIA-held territory.

In the short term it is difficult for India to become a midstream partner. But if processing and refining capabilities are developed in the coming years as part of the National Critical Minerals Mission along along with stalled infrastructure projects like the Kaladan Multi Modal Project and India-Myanmar-Thailand Trilateral Highway, India can be a vital node in emerging supply chains in collaboration with other countries such as Japan and South Korea with which IREL is seeking partnerships with. However, the realisation of this potential depends on how the precarious situation in Myanmar unfolds and how India navigates its relationships with the fighting factions.

From Borders to Ballots: India’s Stake in Myanmar’s Uncertain Future

India has been consistently deepening its engagement with the Tatmadaw, Prime Minister Modi discussed rare earth mining in his recent meeting with General Hlaing on the sidelines of the SCO summit. Another high-level meeting was held in New Delhi in September 2025 during the visit of Myanmar’s General Ko Ko Oo, who remains under U.S. sanctions imposed by the Biden administration along with other ongoing military engagements. India has also committed to sending observers to monitor Myanmar’s upcoming elections, indicating a measure of support for the electoral process.

India’s stance on Myanmar will be shaped not only by its strategic need for critical minerals, especially as China wields dominance over its global supply and leverages it diplomatically, but also by a range of complex challenges. This includes the impact of cross-border insurgencies and narcotics flow in India’s Northeast, as Myanmar is now the world’s largest producer of opium, as well as internal frictions between the central and state governments over the Free Movement Regime, border fencing, and refugee policies.

Although India is positioned as the only functioning federal democracy in the region which makes it an appealing partner to Myanmar’s pro-democracy opposition, it values stability in Myanmar over everything else. Given its close ties with the Tatmadaw, India may face credibility challenges and will need to actively invest in rebuilding political trust with any incoming democratic or partially democratic administration in Myanmar.

The civil war continues to flare between the Tatmadaw, plagued by desertion and low morale, and opposition forces (the shadow National Unity Government, People’s Defence Forces, and ethnic armed organisations), who have come together in an unprecedented manner but have their own sub-national goals. However, the prospects of an absolute win for the pro-democracy opposition forces, where all political factions and armed groups consolidate territorial control, including major cities, and reconcile their differences to establish a cohesive and inclusive government for the entire country, remain grim. Chances of a protracted stalemate or fragmentation into autonomous regional entities are higher.