Overview

• Biden and Putin explore “rules of the road”

• Proof of the pudding: Afghanistan, Iran, Syria

• Russia and China transcend alliance

• Putin skates around the Quad

Biden and Putin explore “rules of the road”

The June 16 Biden-Putin meeting in Geneva – awaited with anticipation in Russia, unease in Europe and scepticism in the US – generated just a sliver of hope for some abatement in the acrimony that has dominated US-Russia relations over the past decade.

Faced with criticism and questioning of the wisdom of his decision (announced in April) to meet President Putin, President Biden had consistently maintained that he wanted see if he and his Russian counterpart could establish “rules of the road” to bring some predictability to the relationship, enabling cooperation in resolving pressing global issues on which their interests converged. On emerging from their four-hour meeting, both Presidents conveyed the impression that a pragmatic engagement was possible.

It was agreed that their Ambassadors would return to their respective stations – they had been withdrawn in March-April. The foreign offices will commence discussions on return of seized diplomatic properties and restoration of staff strengths in their diplomatic and consular missions. It was hinted that foreign ministry officials could work out a compromise for exchange of convicted prisoners – there are two publicly-known cases in each country.

In addition to these relatively low-hanging fruits, the three big decisions were to launch “strategic stability” talks (for arms control), to establish a mechanism to prevent cyber/ransomware attacks from the territory of either country, and (as Russia assumes the chair of the Atlantic Council) to try to reconcile their respective geopolitical interests in the Arctic (clarifying the “rules of the ocean”, as it were).

The Presidents issued a joint statement, agreeing that an “integrated bilateral Strategic Stability Dialogue” would work towards arms control and risk reduction measures. This initiative follows up on President Biden’s decision, almost immediately after assumption of office, to accept the pending Russian suggestion to renew the new START, a treaty which was to lapse in February 2021. Both countries had signalled before the summit that they would be open to a comprehensive review of all strategic weapons – nuclear and conventional, offensive and defensive. The Presidential statement formalized this objective. With the horizontal and vertical proliferation of new generations of weapons technologies, and the fact that the Anti-Ballistic Missile (ABM) and the Intermediate-range Nuclear Forces (INF) Treaties have lapsed, this effort to restrain the arms race is welcome. It would, of course, involve long and tortuous negotiations, also because any comprehensive review of strategic stability will eventually have to draw China’s weapons capability into its ambit.

A bilateral mechanism to discuss cybercrime was another major takeaway, also presenting difficult implementation challenges. President Biden said he handed over a list of 16 critical infrastructure entities (“from the energy sector to our water systems”) as “off limits to attack”, while also drawing President Putin’s attention to the US’s cyber capability to target critical Russian infrastructure. On his part, President Putin told the media that Russian establishments had also been the victim of cyberattacks, many of which had originated from the US. President Biden confirmed that the dialogue will address cyber incidents originating from either country. The key premise here is that “responsible” countries should not only desist from government-sponsored cyberattacks, but also prevent cybercrimes originating from their territories. Ensuring the latter will require close cooperation and sharing of information by the respective cyber agencies and response mechanisms, which could sometimes become tricky, especially because this cooperation has to be ringfenced from cyberespionage – which, obviously, both countries will continue, though (equally obviously) neither will acknowledge it. If a workable template can be evolved for bilateral cooperation, coupled with the threat of targeted retaliation, it would be a major achievement. It is an uphill road.

The US-Russia discord on the Arctic is progressively intensifying, as the region’s resources become more accessible and the Northern Sea Route becomes more navigable for longer periods in a year. The US and other Arctic countries have expressed concern about Russia’s expanding military infrastructure in the region. President Putin said recently that Russia is merely restoring and modernizing degraded infrastructure, including for effective border control, nature conservation, and emergency search and rescue operations. As Russia has recently assumed the Chair of the 8-member Arctic Council, there is likely to be greater urgency in these discussions.

President Biden had promised to take up with his interlocutor issues of human rights and specifically the treatment of opposition activist Alexei Navalny. After the meeting, he said he had done so, but did not provide much detail. In response to a specific question, he said he had conveyed to President Putin that it would severely damage US-Russia relations, if Navalny were to die in prison. This of course falls considerably short of demanding his unconditional release from prison, which earlier US and EU statements have done. In his separate press conference, President Putin dismissed US concerns about Navalny, alleging that he was being propped up and funded by foreign agencies, as part of the West’s regime change agenda in Russia. In response to US remonstrations about the restrictions on the operations in Russia of a couple of US media outlets, the Russians pointed to similar restrictions on two Russian media agencies in the US. This may also be addressed in the dialogue between the foreign ministries. The Biden Administration has declared it will energetically espouse human rights, press and political freedoms everywhere, but pragmatic politics normally results in an inverse correlation between the intensity of such espousal and the tempo of bilateral cooperation.

Both leaders went out of their way to emphasize that the discussions were constructive and business-like, with each trying to understand the other’s perspectives. Disagreement, President Biden said, was not “done in a hyperbolic atmosphere”, commenting that there was too much of that going around. His projection of his counterpart as a sober interlocutor, rationally pursuing his country’s interests, did not go down well with his audience, which is more used to the portrayal of the Russian President as a malevolent and reckless wrecker of the world order. President Putin returned the compliment, describing President Biden as a thorough professional, “completely knowledgeable on all issues”.

President Putin also said that, on the whole, both sides have a pretty clear understanding of the “red lines” of each other. This is an important requirement for effective tension management.

Sensitive to the fact that his decision to meet the Russian President was not particularly welcome in much of Europe, President Biden used his extended European tour to assuage apprehensions. Starting with the Baltic countries and working his way through Poland, Romania and then the other countries, he followed a sequence from the most apprehensive to the least. After the G7, NATO and EU summits, he declared that every one of the leaders had applauded his decision to meet with President Putin. The additional achievement, as highlighted in the post-Summit briefings by US NSA Jake Sullivan, was the convergence President Biden forged with the world’s democracies on China: getting NATO to recognize the security challenge posed by it, and agreement of G7 and EU countries to coordinate efforts to counter and push back China’s “non-market economic practices”.

Grilled by the US media in his post-Summit press conference, President Biden was remarkably frank in divulging his takeaways from his conversation with President Putin. He described Russia’s perception of being “encircled” by the US and its allies, and President Putin’s feeling that the West was “looking to take him down”. However, Russia’s bigger problem, he said, was that it was being “squeezed” by the rising power of China. A Cold War with the US would thwart President Putin’s ambition of reviving Russia’s economy and its status as a great power. President Biden’s conclusion was that self-interest should nudge Russia towards a modus vivendi with the US.

The indications from the above are that the US may have not only embraced the geopolitical wisdom of trying to loosen the Russia-China embrace, but is also making a serious effort to impart this wisdom to its allies. The path to a modus vivendi with Russia will, however, remain rocky. Within the US itself, hostility to Russia (and to President Putin) has bipartisan adherence – and this includes key appointees in the Biden Administration. US-Russia confrontation has boosted US arms sales to Europe and Asia. A number of NATO allies are nervous that their interests may be undermined by a US-Russia détente. A Ukraine denouement would encounter Russian and/or European red lines. The recent failure of a Franco-German initiative for a summit-level EU-Russia meeting is an indication of this. In Russia too, there are elements profiting from a US-Russia standoff – the western thesis that not a single sparrow falls to the ground in Russia without Putin’s knowledge is a somewhat distorted picture of the reality in Russia.

For the present, official Washington has definitely toned down its language on Russia. There are fewer references to Russia’s “reckless” or “aggressive” actions. The Biden Administration has carefully avoided directly implicating the Russian government in recent cyber hacking incidents (though there is increasing pressure on President Biden to retaliate). At the same time, the Russians have been prickly in their reactions to comments by US officials which they perceived as deviating from the understandings at the top level. This appears to derive from the assessment that, while the US President is determined to find a working relationship with Russia, forces may be at work at other levels to undermine this effort.

The climate created by the summit does, however, appear to have facilitated progress in discussions on international issues like Afghanistan, Syria and Libya.

Proof of the pudding: Afghanistan, Iran, Syria

Among the incentives for President Biden to press ahead with an early meeting with President Putin was almost certainly that it may improve the atmosphere for resolution of the various international problems in which the US finds itself embroiled and which President Biden believes is diverting focus from more pressing domestic challenges.

Afghanistan was clearly high on the Biden-Putin agenda. Without divulging details, the US President said his interlocutor had offered “help” in maintaining peace and security in the country. Having precipitately (almost furtively) withdrawn its troops, in the face of repeated warnings from military advisers and intelligence agencies of an inevitable civil war ensuing, the US is quite willing to hand over the poisoned chalice for Russia to handle. This is an area where the US and Russian special envoys for Afghanistan have collaborated closely since 2017, inducting China, and later Pakistan, in an “extended troika”, essentially to bring the Taliban into the mainstream of Afghan politics. It remains to be seen if the resultant foothold that the Russians have gained in Afghan political circles will help in salvaging something from the fast-deepening chaos in that country. India’s consultations with Russia and Iran (among others) have the same objective. Simultaneously, though, the US is engaged with Uzbekistan and Tajikistan on Afghanistan (including to “temporarily” host Afghan collaborators with the US, for whom US visas are under process). The Uzbek and Tajik Foreign Ministers visited Washington recently for talks. Russia would have been less pleased with President Biden’s agreement with President Erdogan for Turkish troops to secure Kabul airport.

If a return to a nuclear deal with Iran gains traction, Russia could be of help, as President Biden acknowledged in his Geneva press conference. Russia played a significant role in the negotiations and implementation of the 2015 deal, including transportation of about 10 tons of low-enriched uranium from Iran to Russia.

Syria is another theatre in which US-Russia confrontation has been playing out, since the Russian military intervention in 2015, which turned the tide in the civil war. Russia’s thrust to bring the entire Syrian territory under the control of the Damascus government has been stymied by Western (and some West Asian countries’) refusal to accept the legitimacy of the Assad government, US troop presence east of the Euphrates, Turkish interests in the bordering Kurdish territory and Israeli desire to rollback Iranian presence in Syria. Despite their conflicting interests, the Russia-Turkey-Iran “Astana group” was instrumental in the formation of a Syrian Constitutional Committee that is to draw up a new Syrian Constitution under the watchful eye of the UN Special Envoy, in terms of UN Security Council Resolution 2254. The process has seen its ups and downs, reacting to shifting interests of the various stakeholders. Harsh Western sanctions against Syria have prevented the Assad government from receiving much needed external economic assistance for the rehabilitation of his war-torn country. In turn, Russia has tried to hinder Western-backed UN efforts to reach humanitarian assistance to north-eastern Syria, by vetoing or delaying UNSC authorisation of the aid corridors. President Biden hinted in Geneva, as well as in an earlier press conference, at possible flexibility in the US position, in return for Russian cooperation on Afghanistan and Iran. After much wrangling, the UNSC recently approved unanimously a proposal to keep one check post open for assistance to north eastern Syria. Significantly, the final text was co-sponsored by the US and Russia. It should be presumed that there is a quid pro quo somewhere for this “concession” by Russia.

Russia and China transcend alliance

The impression President Biden carried away from his conversation in Geneva was that Russia needs a modus vivendi with the US to further its great power ambitions. Its flagging economy and surging Chinese political and economic power are otherwise in danger of reducing it to a junior partner of China. While this may have accurately reflected the tenor of their conversation, the public disclosure of it may have embarrassed President Putin. However, within two weeks of the Geneva meeting, the leaders of Russia and China held a virtual summit, at which they celebrated mutuality of support, eulogized the achievements of the bilateral partnership and hailed the 20th anniversary of the friendship treaty they concluded in July 2001.

A Russia-China joint statement confirmed the intention of the two parties to renew the treaty for a further period of five years from February 2022. It recalls some salient elements of the treaty: inter alia, mutual support, respecting state unity and territorial integrity, non-first use of nuclear weapons, not to target strategic missiles at each other, non-interference in each other’s domestic affairs and working for genuine multilateralism. It describes the political coordination between the two countries, bilaterally and multilaterally, their wide-ranging economic, financial and energy cooperation, and their “stabilizing role in global affairs”, from Korea to Afghanistan, Iran and Syria. “Russia”, it asserts, “is interested in a stable and prosperous China and China is interested in a strong and successful Russia”.

There is the usual litany of complaints about “unilateral coercive measures” (including extraterritorial ones), double standards on human rights, aggravation of global tensions because of the US missile defence systems and withdrawal from arms control regimes. There is a call for constructive interaction to build “an equal and indivisible security system in the Asia-Pacific”. Criticizing the accelerated withdrawal of US and NATO forces from Afghanistan, Russia and China promise to jointly work “to safeguard regional peace, security, and stability”.

Ascending to the next level, the Joint Statement declares that Russia-China relations have reached the highest level in their history. They are not a Cold War-type politico-military alliance: “they exceed this form of interstate interaction”. They are not opportunistic, are free of ideology, involve comprehensive consideration of mutual interests and non-interference in internal affairs, are self-sufficient and not directed against third countries. In short, they are a poster boy for “international relations of a new type” (one of the mantras of President Xi’s Thoughts).

Interestingly, President Putin said (in his opening remarks to President Xi) that the treaty confirms the “absence of mutual territorial claims” and the mutual determination to make the Russia-China border a “belt of eternal peace and friendship”, adding that years of jointly working on the border issue had yielded a result acceptable to both. It is unclear whether there was an immediate provocation for this somewhat out-of-context assertion. From time to time, there is grumbling in the Chinese regional or social media about “unequal treaties” (for example, when the 160th anniversary of Vladivostok was celebrated last year) that forced China to yield about a million square kilometres of natural resource-rich “Outer Manchuria” to Russia, but official Beijing has avoided public articulation of such sentiments (though senior Russian military personnel have privately admitted seeing wall maps in their Chinese counterparts’ offices, which show pre-1858 Chinese borders, including vast areas of the Russian Far East).

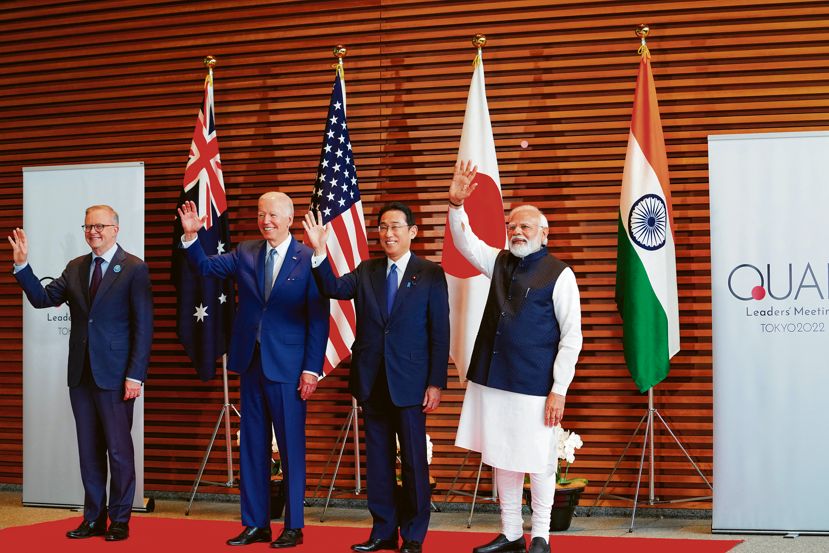

Putin skates around the Quad

During his traditional press interaction (virtual this time) at the St Petersburg International Economic Forum (SPIEF), President Putin responded to questions from a PTI representative about the impact of Russia-China relations on Russia-India relations, and his view of India’s participation in the Quad, which FM Lavrov dubbed “Asian NATO”. About the Quad, he said it was the sovereign right of countries to join any partnership, though such partnerships should aim to achieve common goals, rather than simply align against another country. Russia, he said, is not in this configuration, but it does work closely with both India and China, bilaterally and in organisations like BRICS and SCO. There are issues between India and China, but there are always issues between neighbours, and the leaders of the two countries are responsible, have mutual respect and will find a way to resolve issues between them. Extra-regional powers should not stand in the way of this.

On India-Russia relations, he said they are “of a truly strategic nature”, covering a range of economic issues, energy, and high technologies, the last also including the military-industrial complex, going well beyond commerce to design and production in India of cutting-edge and advanced weapons systems, “probably the only such partner of ours”.

In short, the message is that India and China are both Russia’s best friends – one “more best” in some areas and the other “more best” in others. The irritants for India (and, possibly, for China) may arise in the overlapping segments of these two circles, when both India and China claim best friend priority.

*******

The previous issues of Russia Review are available here: LINK

…………………………………………………………………………………………………………………

(The views expressed are personal)

The Author can be reached at raghavan.ps@gmail.com

…………………………………………………………………………………………………………………