Overview

• The world according to Putin

• The world order and its institutions

• The malaise in international organizations

• Constructive multilateralism

• Arms control

• Relations with Germany

• Russia-China relations

• US elections

• India-Russia relations

The world according to Putin

It is universally believed that President Putin has unchallenged control over Russia’s foreign, defence and security policies. He makes frequent public pronouncements on these issues, announcing, clarifying or justifying policy decisions. In many cases, Foreign Minister Lavrov provides explanatory notes and adds in the harsher messages, which Putin generally avoids. This issue of the Review focusses on some of their recent pronouncements.

The world order and its institutions

Putin has consistently argued that the institutions of global political and economic governance established after World War II are essentially sound and efforts to degrade or bypass them should be firmly countered. Quite naturally for the leader of a country widely portrayed as a fading power, he jealously defends the trappings of power that Russia has inherited from the post-War dispensation. He has elaborated on this in recent speeches and interviews.

He recalls that the post-war world order was, in effect, established by three victorious countries: the Soviet Union, the United States and Great Britain. The role of Britain has changed since then. The Soviet Union may not exist, but Russia is not a waning power; addressing those who are waiting for Russia’s strength to wane, he says, “the only thing we are worried about is catching a cold at your funeral”.

In his UNGA speech, Putin said the UN Security Council should continue to serve as the cornerstone of global governance, which cannot be achieved unless the permanent members of the Security Council retain their veto power. This right of the five nuclear powers, the victors of the Second World War, “remains indicative of the actual military and political balance to this day”. He argues that this “essential and unique instrument” has helped prevent direct military confrontation between “major States”, provided the opportunity for compromises and preserved international law against “arbitrariness and illegitimacy”. Elsewhere, he says the preservation of the post-War international order enjoys broad support in the world.

In Russia’s view, therefore, the permanent members of the UN Security Council, “who have been bearing particular responsibility for international peace and security for 75 years”, should take the lead to “reaffirm key principles of behaviour in international affairs” and seek ways to effectively address today’s most burning issues. Putin has offered to host a G5 summit to kickstart this process; Russian officials say the other four major powers have agreed to attend the meeting, once the pandemic has blown over.

Considering that a 3-2 polarization among the P5, including totally differing perspectives on “key principles” of international behaviour, has virtually paralyzed the UNSC and other international organizations, it is difficult to see what such a summit will achieve and how it can realistically pretend to truly represent the spectrum of political and economic interests in today’s world. It can, at best, burnish Russia’s credentials as a major world power.

Even while asserting the predominance of P5 in global governance, Putin acknowledges that the Security Council should be more inclusive of the interests of all countries, recognize the diversity of their positions and base its work on achieving the broadest possible consensus among States. Hence, the idea of adjusting the institutional arrangement of world politics is “at least worthy of discussion”, because the correlation of forces, potentialities and positions of states has seriously changed in the past three or four decades. The United States cannot claim “exceptionality” any longer. China is moving quickly towards superpower status. Germany is moving in the same direction. The roles of Great Britain and France in international affairs has undergone significant changes. And powerhouses such as Brazil, South Africa “and some other countries” have become much more influential.

These statements and initiatives clearly indicate Russia’s approach to UN reform. The present system has worked for it, particularly in the current scenario, where the permanent seat and the veto have insulated it from the worst of the western political and economic measures. The bottom line is, therefore, that Russia will support a process of UN reform, only when it can be assured that the final outcome will preserve its presence and veto at the top table of the new structures.

The malaise in international organizations

Even while asserting the relevance of the post-War structures of international governance, Putin (and FM Lavrov, much more trenchantly) has lamented that international organizations often display “ideological prejudices” and become political tools in the hands of some states. The Russian grouse is also that the international order established after the World War, which – as Putin and FM Lavrov repeatedly affirm – “suited everyone”, is being sought to be replaced by a different “rules-based order”, where the rules are made to suit the political interests of a few. FM Lavrov recently identified two manifestations that are undermining the “international” character of international organizations: “privatization” of their structures and moving “inconvenient” matters out of the UN system into parallel multilateral forums.

As an example of the first, the Russians draw attention to the amendment of the charge of the technical secretariat of the Organisation for the Prohibition of Chemical Weapons (OPCW), empowering it to identify perpetrators of violation and attributing responsibility. The Russians allege that this contravenes the provisions of the Convention and enables the secretariat, manned mainly by citizens of western countries to make politically-motivated (rather than technically validated) pronouncements.

The Russians tried to establish their case about OPCW’s bias by arranging an Arria formula meeting at the UNSC on the OPCW report on the alleged Syrian government use of chemical agents in Douma in 2018. A senior OPCW expert involved in the original report testified that he had been pressurized to change his report, which originally cast considerable doubt on the use of chemical agents. Other experts also weighed in to express doubt about the correctness of the final report. This effort got no traction, nor did the initiative to invite former OPCW DG Bustani to talk to the UNSC.

Lavrov said such “privatization” of secretariats can be seen in a number of UN organizations, where senior positions are occupied by Western officials, who pursue “blatantly one-sided policies”.

Among many examples of the second manifestation, Lavrov cited the example of the French-sponsored “International Partnership against Impunity in the use of chemical weapons” within the EU, in which (in Lavrov’s words) a “narrow circle of soul-mates” will establish “facts” and approve sanctions against the guilty, based on these unilaterally established “facts”. Lavrov said it was quite likely that the poisoning of the opposition activist Navalny (see Review, 9/20) would be handled in this manner. According to him, similar partnerships are under creation on the freedom of journalism and information in cyberspace. The basic point is that groups of countries seek to further their interests in smaller multilateral groups, when they are blocked from pursuing them in the larger UN system, because of the impasse within it.

Constructive multilateralism

Putin has provided examples of “constructive” multilateral behaviour: the Shanghai Cooperation Organisation, which has contributed to the settlement of territorial disputes and strengthening stability in Central Eurasia; the Astana format (Russia-Turkey-Iran), which was instrumental in taking the political and diplomatic process in Syria “out of a deep impasse” and the OPEC Plus, which is an effective tool for stabilising global oil markets.

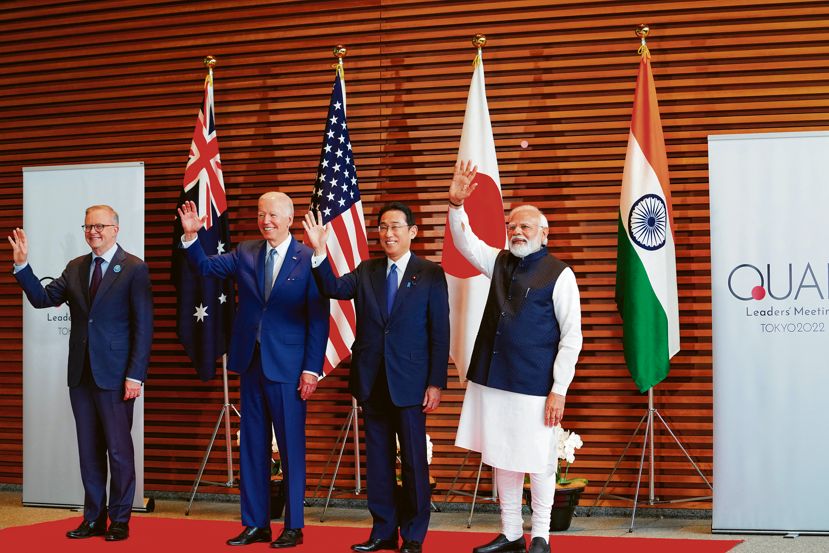

Putin and Lavrov have lauded such approaches as more relevant in a fragmented world, where multilateralism should be understood not as total inclusivity, but as an instrument to involve parties that are truly interested in solving problems. However, Lavrov has harsh words for multilateral activities that do not involve Russia. In an obvious reference to Indo-Pacific initiatives, he says nothing good can come out of efforts where outside forces “crudely and shamelessly intervene in a process that affects a group of actors perfectly capable of agreeing among themselves … solely for the purpose of flaunting their ambition, power and influence”.

This is par for the course in a bitterly polarized world: my multilateralism is constructive; yours is crude geopolitical manipulation.

Arms control

The ongoing US-Russia negotiations on the renewal of the new START (which lapses in February 2021) drew elaborate comment and periodical interventions from President Putin. He regretted the withdrawal of the US from successive arms control and confidence-building agreements: the ABM Treaty, INF Treaty and the Open Skies Treaty, and blamed it for the current impasse on START.

Particularly on the INF Treaty, he contrasted the manner of US withdrawal with that from the ABM Treaty. Then, he said, the United States “acted openly, directly and bluntly, but honestly”. Here, they came up with accusations of Russian violations. If there were violations, he said, they were on both sides, and could have been addressed through a better verification and monitoring mechanism, instead of this political grandstanding.

On START, negotiations between the two countries were escalated from the level of their Special Envoys to that of their National Security Advisors on October 2. The US Special Envoy announced thereafter that an in-principle agreement had been reached “at the highest levels” to extend START, along with a “gentleman’s agreement” to freeze all nuclear weapons, including those not covered by the strategic arms-control treaty, subject to verification details to be worked out. Lavrov rejected this description, saying there was still no agreement on such a freeze or the new weapons systems to be included. Moreover, Russia was not open to bringing into the equation its tactical nuclear weapons, without taking into account the tactical weapons deployed by the US in European NATO countries.

On October 16, Putin announced his decision (as recorded on the Kremlin website) to offer to the US a one year extension of START without any conditions or revisions. The US NSA swiftly rejected this, saying it does not meet the US demand for freezing all other nuclear arsenals for the extension period. Then, on October 20, Russian MFA announced Russia is willing to undertake, jointly with the US, a “political commitment” to freeze the number of nuclear warheads during this period, provided the US did not make any additional demands. This period could be used for comprehensive bilateral negotiations on a nuclear and missile arms control regime, addressing “all factors affecting strategic stability”. The US Special Envoy responded positively, declaring a deal was “very, very close”, but pointed to the need for a rigorous verification regime. Russia, as Lavrov had earlier told the media, is not open to an intrusive verification regime of the kind that had been agreed with the Americans in the 1990s. Both Russian and US media speculated that this urgency on the US side and the apparent willingness for compromise on the Russian side were driven by Trump’s keenness for an arms control deal that might help his re-election efforts and Russia’s keenness to help him. This was an overestimation of the electoral importance of the deal and underestimation of the complexity of the issues involved.

The other issue which the Americans had been persistently raising was bringing China into the arms control regime. When American officials publicly hinted recently that Russia would be happy to see this, Lavrov reacted angrily that they were simply trying to drive a wedge between Russia and China.

Putin dealt with this subject in a more elaborate manner. He said that Russia is not averse to bringing China into these negotiations, but it is not for Russia to attempt this. China, he said, had some very relevant points: its nuclear arsenal is less than half of that of the US or Russia. Is it being asked to freeze this inequality? It is, he said, the sovereign right of a 1.5 billion strong nation to decide on its security policy.

In another statement on October 26, President Putin reiterated the earlier Russian proposal for a moratorium on deployments of ground-based intermediate- and shorter-range missiles in the European theatre, as long as US-manufactured missiles of similar classes are not deployed in the region. NATO countries were also called upon to consider declaring a reciprocal moratorium. He added that Russia is willing to consider specific options of reciprocal verification measures to remove existing concerns, particularly covering the Aegis Ashore systems deployed at US and NATO bases in Europe, as well as 9M729 missiles in Russia’s Kaliningrad. Russia committed not to deploy its 9M729 missiles (the principal culprit in the US allegation of Russia’s INF Treaty violation) in European Russia, if NATO reciprocally precludes deployment in Europe of weapons prohibited under the INF Treaty. The significant addition to the Russian proposal was the call to “all parties concerned to search for patterns of maintaining stability and preventing missile crises “in a post-INF world” in the Asia-Pacific region.

These proposals were immediately dismissed by the NATO Secretary General and some European countries, though France said it would study them.

Relations with Germany

As mentioned, Putin described Germany as a major global power. In a separate reference, he talked about the “very good” relations with Germany over the decades, recalling how the Soviet Union played a decisive role in the re-unification of Germany, though some of Germany’s allies had opposed it. [Both Britain’s Thatcher and France’s Mitterrand had quietly conveyed to Gorbachev that, notwithstanding their public posture, they would be quite happy if he opposed German reunification.] Putin pointed out that Germany is Russia’s second largest trade partner and over 2,000 German companies are present in Russia.

Even as Putin painted this rosy picture, FM Lavrov pointed to a regressive trend in German-Russia relations. He quoted German media on “a new Eastern policy” being developed by elements “close to the German government”, which argues for a reversal of policy towards Russia, unless Russia falls in line with the western “rules-based order”. Lavrov’s dire conclusion was there is a resurgence of arrogance in Germany, which is now “becoming the lead player in ensuring a strong and lasting anti-Russia charge in all processes underway in the EU”.

Russia-China relations

One of Putin’s most significant pronouncements (particularly, but not only, from an Indian perspective) was his response to a question on the state of Russia-China relations. He said he would not mention “specially privileged” relations, because it is not the name but the quality of relations that matter. It is a relationship of deep trust, with durable, stable, and effective ties across the board. Calling President Xi a friend, he said they were in regular consultation and work together on a range of areas including aviation, nuclear power, infrastructure, hydrocarbons and significant military-technical cooperation involving sharing of technologies. Asked further if a military alliance is possible, Putin responded it may not be necessary, but is certainly imaginable, “in theory”, quoting the existing level of joint military exercises, sharing of technologies and “other sensitive issues” of which he cannot speak publicly. The final shot was that Russia-China defence cooperation is boosting the defence potential of the Chinese army, which is in the interest of both Russia and China. So far, therefore, he said, “we have not set that goal for ourselves, but in principle we are not going to rule it out either”.

US elections

Putin was asked about being blamed for interference in the US elections and Biden’s description of Trump as “Putin’s puppy”. He was also asked about his preference between the two Presidential candidates.

He trotted out the politically correct response that Russia does not interfere in the US elections and will work with any elected US President. He said descriptions of Trump as “Putin’s puppy” only flatter Russia, by ascribing to it “incredible influence and power”.

He noted that, though Trump has consistently advocated improving Russian-American relations, a bipartisan US consensus for containing Russia limited his options. There have been some positive developments in bilateral relations (like expansion of trade and cooperation in managing the global energy market), but the Trump Administration has also imposed the harshest sanctions against Russia, taken the drastic step of withdrawing from the INF Treaty and is now threatening to withdraw from the Open Skies Treaty.

Noting the sharp anti-Russian rhetoric of Biden, Putin said Russia has become used to it, but the liberal ideals of the Democratic Party provided some “ideological basis” for Russia to develop contacts with a Biden Administration. He added that Biden’s expressed support for the extension of the New START opened up a potential area of collaboration.

Putin sent what the Kremlin called “a message of encouragement” to Trump, wishing him and the First Lady a speedy recovery from Covid, expressing the conviction that his “inherent vitality, vigour and optimism” will help him overcome the virus.

India-Russia relations

Like the significance in the Sherlock Holmes story of the dog that did not bark in the night, it was significant that Putin did not mention India in his various pronouncements. Talking of influential powerhouses, he mentioned Brazil and South Africa (!), but not the other BRICS partner, India. This is a curious omission: normally, India figures along with China in his descriptions of economic powerhouses. It is possible that it is an expression of disappointment at the increasing intensity of India’s US embrace or at slow progress in India-Russia initiatives (or both). The explicit references to sharing of military technologies with China, strengthening China’s defence potential, the possibility of a military alliance and, finally, the remark that the quality of relations is more important than descriptions such as “specially privileged” may all be messages directed as much at India, as elsewhere. Time will tell whether this is an overinterpretation.

*******

…………………………………………………………………………………………………………………

(The views expressed are personal)

The Author can be reached at raghavan.ps@gmail.com

…………………………………………………………………………………………………………………